IMPORTANCE OF GROUNDWATER IN THE HILL COUNTRY

Managing groundwater in the Hill Country is challenged on multiple levels and different perspectives. From socio-economic concerns of population growth and difficult economic times, changing demographics, varied approaches to accessing news and civic involvement, over-drafted aquifers, unique and fragile ecosystems; and multi-level water governance through state, county, and groundwater districts, groundwater is definitely under pressure and increasingly frangible rather than resilient as a water resource. The critical, time-sensitive needs of Hill Country groundwater is the core of this project. Understanding the issues, linkages, and the benefits and worth of protecting the water systems is no small task. However, without the ongoing efforts of studies with tangible results and accessible information, it is likely that groundwater and its linked systems will continue to be deleteriously impacted in the foreseeable future.

GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT IN TEXAS

Groundwater management begins with identification of aquifer locations and characteristics. Throughout the years, many geologic, geophysical, and hydrogeologic studies of rock formations and the associated aquifers have contributed to in-depth understanding of the aquifers in Texas. This information was summarized for each aquifer by the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), the state agency charged with water planning.

Groundwater is a major source of water in Texas and the Hill Country. There are 13 major and 20 minor aquifers; in the Hill Country, the major aquifers are the Edwards and the three water-producing zones of the Trinity.

TWDB maps depict the 9 major and 21 minor aquifers. These aquifers span many counties and most of the major aquifers extend beyond Texas borders. All have distinct characteristics and features, such as water chemistry, and flow regimes. Managing groundwater in Texas, therefore, predominantly occurs at the local and county level through groundwater conservation districts.

Groundwater is managed under various policies and approaches in most US states, and Texas is no exception. However, Texas has some unique regulations that are not used in other states. This can result in challenges when it comes to management of the resource. Approaches and regulatory management in Texas include:

- Landowner well management under “rule of capture”

- Groundwater conservation districts (GCDs)

- Groundwater management areas (GMAs)

- Priority groundwater management areas (PGMAs)

- Statewide water planning through Regional Water Planning (RWP)

Major Aquifers in Texas. Source: TWDB Maps and GIS Data Minor Aquifers in Texas. Source: TWDB Maps and GIS data

Landowner well management through “rule of capture” and exempt wells: Since the 1904 court case Houston & Texas Central Railway Co. v. East (98 Tex. 146, 81 S.W. 279), the rule of capture, also known as the “law of the biggest pump,” has been part of the Texas groundwater management landscape. Generations of landowners installed wells on their land with the right to pump an indeterminate amount of groundwater. Subsequent case law established exceptions to the rule of capture – pumping cannot intentionally injure a neighbor, is not intentionally pumped so as to waste groundwater, and cannot cause land subsidence.

Exempt wells are those by law that do not fall into regulated categories of wells. In Texas, exempt wells are generally installed for domestic and livestock use and pump less than 25,000 gallons per day (gpd). Other US western states have similar rules for exempt wells. As these wells have not historically been part of a state’s water management program, the total number and pumping capacities can only be estimated. Therefore, their impacts on an aquifer is difficult to quantify and manage.

Groundwater conservation districts (GCDs): Texas has stated that these districts are the State’s preferred method of groundwater management, thus supporting local control of groundwater at the district and county level. These districts have been in existence for decades; the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District No. 1 was created in 1951. In general the GCDs are authorized under Texas Water Code Title 2, Chapter 36 (PDF).

Currently there are 97 GCDs and 3 special districts (the Edwards Aquifer Authority, the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, and the Fort Bend Subsidence District). Each GCD has its own enabling legislation and may have slightly different rules and approaches to managing groundwater in that district.

- FAQs about GCDs: The TWDB’s Facts Sheet

- As the GCDs have individual rules and it can be difficult to track them all, here is a link to each Hill Country GCD: Links to Hill Country Groundwater Conservation Districts sites

- For more information about GCDs in Texas, see Texas Association of Groundwater Districts.

Groundwater Conservation Districts. Source TWDB Maps & GIS Data

Groundwater Management Areas (GMAs):

To better support agreements on how to manage groundwater in the individual aquifers which may be located beneath 10 or 20 GCDs, the State created Groundwater Management Areas based on GCDs, counties, and generalized aquifer boundaries at the land surface:

To provide for the “conservation, preservation, protection, recharging, and prevention of water of groundwater,” the Texas Legislature authorized the creation of GMAs in 2001. The Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) created 16 GMAs in 2002. The areas of the GMAs are roughly those of the state’s major aquifer modeling areas, with modified boundaries to adjust for GCDs within each groundwater management area.

The GMAs do not serve as oversight for the GCDs within their boundaries. Rather, the individual areas utilize groundwater availability models within the GMAs to establish current aquifer conditions and future projections, called “desired future conditions” or DFCs. GMA 9 is located in the Texas Hill Country.

An important part of managing the aquifers through local control is the evaluation and determination of Desired Future Conditions (DFCs). Such DFCs are adopted by a 2/3 vote of all the districts in a GMA. In the last few years, many districts and GMAs have been reviewing and revising their groundwater models to determine the best DFCs per GMA. In the Hill Country GMA 9, the most recent DFC of allowing an average 30-foot drawdown in the Trinity aquifer has come under much dispute by different organizations. Such disagreements can be brought to the TWDB and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) which have processes for appealing DFCs.

Priority GMAs: PGMAs were authorized by the Texas Legislature to deal with areas that may have experienced, or are likely to experience, significant groundwater problems such as water shortfalls, land subsidence due to groundwater pumping, or contaminated groundwater. The PGMA management is overseen by TCEQ, TWDB, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD). Currently there are eight PGMAs. Of interest to Central Texas is the PGMA designation for portions of Hays, Comal, and Travis counties.

To learn more about PGMAs, visit the TCEQ webpage.

Statewide water management through Regional Water Planning: Thanks to proactive planning in the 1990’s, Texas has an active statewide planning process. Sixteen Regional Water Planning Groups (RWPGs) were established and reflect regional water uses (for example, the Panhandle’s reliance on the Ogallala Aquifer as well as Lake Meredith and the Canadian and Red Rivers), portions of river basins and their communities (an example is the Lower Colorado River Basin).

Groundwater supplies in the 16 RWPGs are estimated to decrease 30%, much of that due to overpumping in the decreasing levels of the Ogallala Aquifer and reductions in the Gulf Coast Aquifer to prevent land subsidence.

A list of the RWPGs:

- (A)Panhandle Region

- (B) Red River Basin Region

- (C) Dallas-Ft Worth Region

- (D) North East Texas Region

- (E) Far West Texas Region

- (F) Midland-Odessa Region

- (G) Brazos Region

- (H) Lower Trinity River Region

- (I) East Texas Region

- (J) Plateau Region

- (K) Lower Colorado River Region

- (L) South Central Texas Region

- (M) Rio Grande Region

- (N) Coastal Bend Region

- (O) Llano Estacado Region

- (P) Lavaca Region

These RWPGs have now been through 3 planning cycles. The data and information about water use, including groundwater, are incorporated into the State Water Plan. The most recent draft for 2012 is online.

Key findings of this statewide planning and analysis of water resources are:

- The state’s population is expected to grow by 82% over the next 50 years, from 25.4 million to 46.3 million.

- Water demands may increase only around 22%. While agricultural uses over the next 50 years are expected to decrease, municipal water demands are increasing.

- Texas water supplies are currently from surface water (reservoirs and rivers), groundwater, and reuse of water.

- In 2003, groundwater provided 59% of the 15.6 million acre-feet of water used in the state. This usage is expected to continue – albeit at decreasing levels – through the year 2060.

- Available groundwater, particularly in the Ogallala Aquifer, is expected to decrease by about 30%.

- In times of drought, Texas does not have enough water for all demands, including support of riparian, riverine, and spring-fed ecosystems.

- Strategies to address this gap are water conservation measures, new reservoirs, new wells, increased water reuse, and desalination.

- Implementing additional water supply strategies will not be free. The Draft 2012 Water Plan estimates that capital costs for the strategies are $53 billion.

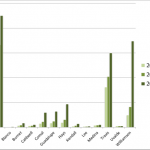

Demands on groundwater will increase as population in the Hill Country increases. As shown in this graph, between 2000 and 2010 the population growth in 14 Hill Country counties experienced the highest increases in three counties with major metropolitan areas Census. These changes and other factors aid in making growth projections over the next few decades.

Population is expected to double over the next 50 years putting more of a demand on municipal uses. Water used for agriculture, currently the biggest user, is projected to decrease due to conservation measures. The water saved in the agriculture sector will most likely be allocated for municipal uses.

However, charts and trends do not tell the entire story. Increases and decreases in groundwater levels affect base flows to rivers and creeks and springs. The interactions between groundwater and surface water are not only flows and storage but also changes in water quality. Some cities currently depend on groundwater sources for potable water, as do certain ecosystems. As demonstrated by the increase in visits to state parks as well as a heightened interest in the outdoors, Texans will continue to support their natural treasures. We all need to improve our knowledge of water and natural resources, and keep Texas in great shape!

This webpage has its foundation in The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment’s research on groundwater.